Mark Maynard talks mental illness, stigma, suicide and personalized treatment options with John Greden, Executive Director of the U-M Depression Center

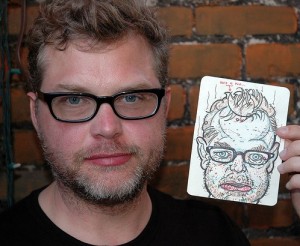

Mark Maynard

It’s Hard to See the Screen Through the Tears

In the immediate aftermath of Robin Williams’ death, there was a great deal of talk in the press about suicide, depression, and the fact that the two, all too often, go hand in hand. As someone who not only suffers from OCD and depression, but who has also lost several members of his family to suicide, I was hopeful that the conversation would continue, and that research dollars would begin flowing in for mental health researchlike they did this summer for ALS. Sadly, though, I haven’t seen much in the mainstream press over the past month. That doesn’t mean, however, that good things aren’t happening. In fact, there’s going to be a fundraiser next Wednesday night at the Michigan Theater hosted by the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC). Tickets to the event, which is being billed as a “Tribute to Robin Williams,” are just $10 a piece, and I expect that it’ll be a good time. So, if you’ve ever wanted to sit in a beautiful, historic theater and watch Dead Poets Society surrounded by people who care deeply about depression and suicide, here’s your chance. I’ll be there, along with Dr. John F. Greden, the founding chairman of the National Network of Depression Centers and executive director of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Depression Center, so you’ll be in good company… Speaking of Dr. Greden, I sent him a few questions last night and he was nice enough to step away from his important work and answer. Here’s our conversation.

MARK: Before we get started, I’d like to ask you a little about your history. It’s my understanding that it was your idea in 1999, while serving as Chair of the University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry, to establish the University of Michigan Comprehensive Depression Center, the entity which you now run as executive director. What was it that made you think that Michigan needed a Depression Center, and how did you sell the idea to the Regents?

JOHN: Easy answer, Mark. Clinical depressions and bipolar illnesses, which are brain disorders, occur in 1 of every 6 of us. They are really, really common. They also start young, between 15 and 24, but most are undiagnosed. Then, if untreated, they keep coming and going, but get worse each episode. They are the primary cause of suicides. Not a pretty picture. So it should not be surprising that they lead the world in burden of disease and disability and are second in financial cost among ALL illnesses. Regarding Michigan, clinical depression all by itself is the second or third highest cost of disability. The Regents are bright people. It was not a difficult sell.

MARK: After the Depression Center was launched, you then went on to found the National Network of Depression Centers in 2007, which has as its members 21 institutions across the United States doing work in the field of mood disorders. Why, in your opinion, was such an entity necessary? Was it primarily to coordinate fundraising activities, your sense that there was unnecessary redundancy in the work taking place across our nation’s leading research institutions, or something else altogether?

JOHN: It actually wasn’t started to promote fundraising. It was done so that we could develop better diagnoses and safer, better treatments. And let me be honest; I copied the concept after the nation’s network of cancer centers. The only way for us to really understand these brain illnesses is to be studying tens of thousands of people over long periods of time, so we needed a network to work together. That proposal was actually part of the original model that I presented to the Regents.

MARK: What was it about depression that first interested you? Why did you choose this as your life’s work?

JOHN: Great question. When I was a first-year medical student, I actually did a project where I interviewed women in Minneapolis who had been depressed. Apparently the interest was there beforehand. I love understanding stress, knowing how it impacts the brain, and recognizing how much people with depression suffered, I was hooked on trying to find better treatments.

MARK: How has the field evolved since you first began studying depression?

JOHN: OH, MY GOSH! We have learned so much, and we are learning more every year. The brain is our most-fascinating organ, and this field brings together so many things — genetics, family history, trauma, stresses, sleep, hormones, substance abuse, family, medications, psychotherapies, and many others. We have learned there are different causes of depressions so we need to find the treatments that work for each of these different causes — so-called personalized treatments.

MARK: I’m curious as to how you quantify the problem of depression in America today. We read about loss of productivity due to depression, and we read about the numbers of lives lost due to suicide, but I suspect there are other ways to think about the impacts and costs. Are there other metrics being tracked?

JOHN: Indeed there are. Workplace or student productivity is one measure and it IS impaired, more by depression than almost any other illness. Another metric, harder to measure but important, is “presenteeism,” which means someone with depressions or bipolar illnesses may be at work, but working very inefficiently. Medical costs are yet another measure. The New York Times several months ago referred to clinical depressions as the “Half-Trillion Dollar illness.”

MARK: Full disclosure, I was first diagnosed as having OCD at UM over 20 years ago, when I was a student, and, over the years, although I’d classify my case manageable, I’ve maintained a relationship of sorts with the University, having, for instance, gone through a group program with Joe Himle the better part of a decade ago. For what it’s worth, I’d like to let you know that, for the most part, my interactions have been positive. I know it can’t be easy to provide services in this area, given the things that many of us coming through your door are dealing with, and I’ve appreciated the efforts your team has gone to in order to create an environment conducive to working on these issues that we face.

JOHN: Mark, three things come to mind. First, thank you for being forthright. When we can share as you just did, it is a powerful force for overcoming stigma. Silence is deadly. By saying what you did, you have helped others. Second, Joe Himle and many others are great and I’m so glad that the treatments have helped. Third, an important message for everyone. When something helps any of us — medications, psychotherapy, exercise, whatever — keep it going. Don’t stop because you think something has passed. Sadly, these illnesses are generally long-term. I don’t like the word chronic, but if untreated, they tend to come back.

MARK: I don’t know how indicative my experience was, but I cannot tell you how much I appreciated, as a young adult, who really thought that he was losing his mind, being able to walk into a clinic and having someone diagnose my problem, and explain that, no, I wasn’t losing touch with reality, but just suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. It didn’t make it any less painful, but being able to identify what I had was hugely important for me. And I suspect it’s the same for most people. The truly terrifying thing, from my experience, is not knowing what your mind is doing and why.

JOHN: Well stated. It IS terrifying. Which is why those experiencing whatever illness need to learn as much as they can, need to have wonderful and supportive families and friends, and need to get the clinical help that attains and maintains wellness. These illnesses ARE treatable.

MARK: What, in your opinion, is the most impactful thing that we could do right now to help those suffering from depression? Where, in other words, do you think that we could get the most bang for the buck, given the world in which we live today? Would it be early detection? Would it be diminishing the stigma associated with having a mood disorder? Would it be the development of new drugs? Would it be the popularization of alternative approaches, like meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, etc?

JOHN: If I may be so bold to suggest that it is all of the above that are linked together and become the routine approach for everyone that is suffering, whether in a College Student Health Service, an Obstetrician’s office, a workplace setting, or a psychiatrist’s or psychologist’s office. We need to screen earlier, since these problems are treated more effectively when caught early. We need to develop the personalized treatments that work for my causes. “One size treatment will never fit all.” We need to maintain adherence and wellness. To do any of these we need to counteract stigma — once and for all. In reality, stigma is misunderstanding… ignorance about the causes. Let’s bury it. Finally, we need a network to create the sample sizes that will provide us with the knowledge we need, such as the NNDC.

MARK: Do we, in your opinion, rely too much on drugs as a first line treatment? Or is that, based on your experience, the best way to deal with the situation, given the huge number of people suffering? Is it best to just prescribe Prozac, or any of the similar drugs currently on the market, see who responds, and then focus our limited resources on those who don’t see any improvement?

JOHN: Medications are not necessary for every case. One size treatment doesn’t fit all. But medications are essential for many. A key point, not well understood, is that medications and psychotherapy actually work best in combination for those who need them. We need to stop the argument about whether it is one versus the other. They help each other. While many people consider me a bit of a psychopharmacologist, I think everyone who is depressed benefits from cognitive therapy, mindfulness and other evidence-based therapies.

MARK: In addition to treating people with depression, members of your staff at the Depression Center also conduct research? What research being done right now, if I can ask, are you most enthusiastic about?

JOHN: We are looking at almost everything that has potential to help us understand causes, such as genes; brain imaging; sleep; stress; trauma; substance abuse; the effect of exercise; how medications work; using smart phones to help monitor mood states and maintain wellness; creating stem cells from skin biopsies to study the neurons of bipolar patients as part of the Prechter Bipolar Projects; how to counteract stigma with videos; working with veterans and military personnel to reduce suicide risk; I could go on, but I think you get the picture.

MARK: I understand that you have an event coming up later this week at the Michigan Theater. What is is that you’ll be doing?

JOHN: The screening of the “Dead Poets Society,” in tribute to Robin Williams, is coming up soon on Wednesday, November 19th, at 7:00 PM, at the Michigan Theater. This is our very first awareness raising and fundraising event for the NNDC. We wanted to do something unique and accessible for the most people. As you know, the world-renowned comedian and actor Robin Williams died of suicide. His associates indicated he had been suffering from a severe episode of depression. Because it is not well-known that depressions and bipolar illnesses are the underlying causes of perhaps 75% of deaths by suicide, the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC) has set a goal of trying to decrease suicide rates 20% by 2020. Mr. Williams’ death was a tragedy for his family, friends, fans and society and a very public example of the need for a much greater national effort and call to action to address depressions and the all too many related deaths by suicide in our country.

To help that to happen, we must first mobilize the steps that are at our disposal.

First, use the exciting scientific tools we now have, such as genetics, pharmacogenomics, brain imaging and others, and conduct long-term studies among thousands with depression and bipolar illnesses, not 10s or 20s.

Second, develop evidence-based clinical biomarkers, the laboratory tests that will enable us to differentiate one cause from another.

Third, emphasize public-private partnerships between academia, industry, biotech firms, the National Institutes of Health and foundation-funding agencies to develop new individualized interventions for the underlying causes.

And fourth, conduct the clinical trials necessary to guide clinicians of all disciplines who treat those who suffer.

The National Network of Depression Centers was formed to respond to these challenges. More than 500 members from 21 academic medical centers are united in efforts to advance the research and treatment of mood disorders and orchestrate a national action plan. The Bay Area, where Robin Williams resided, hosts two Centers of Excellence – one at UC San Francisco and one at Stanford University.

But the NNDC and its individual centers cannot do it alone. Williams’ death raised public awareness. Had his depression improved and had he survived, he might have educated us, encouraged the needed research and clinical investments while simultaneously making us laugh. That opportunity is lost, but his untimely death now screams for a change of course. He would want us to join hands to help find the right treatments for the right people at the right time. Cancers and cardiovascular centers have followed that pathway with often dramatic improvements. The time has come for us to do the same for depression and bipolar illnesses.